domingo, outubro 31, 2004

Bush, Kerry sprint to the finish

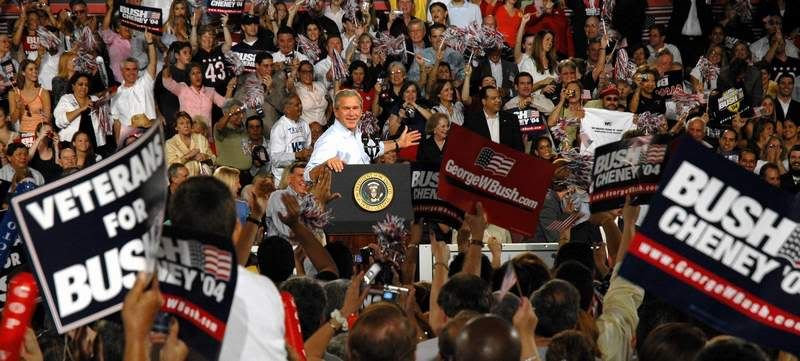

Bush in Miami today. Photo by Rui Ferreira

Candidates hit Ohio, Florida on pre-election Sunday

(CNN) -- The presidential candidates began a 48-hour sprint to Election Day on Sunday, kicking off the day's battleground tours of Ohio, New Hampshire and Florida.

Democratic nominee Sen. John Kerry began with remarks at a predominantly African-American church in Dayton, Ohio, while President Bush started with a rally in Miami, Florida.

Kerry talked about choices in the election to an audience of more than 1,000 worshippers at the Shiloh Baptist Church, Reuters news service reported. "It is a choice about what kind of country and society we'll have."

In Miami, Bush spoke both Spanish and English to his audience, which included many Cuban-Americans and opponents of the regime of Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

"Over the next four years we will continue to press hard and insure that the gift of freedom finally reaches the men and women of Cuba," Bush said, provoking loud applause and chants of "Viva Bush!"

The president is to remain in Florida for much of Sunday, with three campaign stops as part of his effort to win the state's 27 electoral votes. (Electoral College)

In 2000, the Sunshine State clinched the election for Bush, after a month of recounts and court challenges. (Showdown states: Iowa, Ohio, Minnesota, Florida)

Bush's second Florida appearance Sunday was in Tampa. Bush is to make his third stop in the battleground state in Gainesville, before ending the day in Cincinnati, Ohio, where the Bush campaign is hoping to head off any gains in Kerry's popularity.

From Ohio, Kerry follows on Sunday a route to New Hampshire and finally in Florida, where a rally is set for Tampa on Sunday night, just a few hours after Bush was scheduled to depart. (CNN.com's Candidate Tracker)

Far to the west, in Hawaii, as polls showed the presidential race there getting closer, Vice President Dick Cheney was scheduled to campaign Sunday in the Aloha State. He follows on the heals of former Vice President Al Gore, who attended pro-Kerry rallies there on Friday, appealing for Hawaii's four electoral votes. Both Hawaii and New Hampshire have four valuable electoral votes. (Showdown state New Hampshire)

On Saturday, the presidential candidates again devoted their attention to voters in key battleground states, pushing their domestic agendas and underscoring their strategies to fight terrorism.

Kerry spent the morning in the showdown states of Wisconsin and Iowa before landing in Warren, Ohio. Kerry has made more than 20 visits to the state since March. Polls show him gaining on President Bush, though the race between the two candidates remains too close to call.

During the Ohio rally, Kerry urged voters to remember the importance of their choice Tuesday.

"Join with me on Tuesday and we'll change the direction of America," Kerry said to the crowd. "You get to hold Bush accountable for the last four years and set this country on the right track."

He also used the issue of national security to say that what he called Bush's mismanagement of the war on terror has put the United States and its troops at risk.

"I will wage a smarter, tougher war on terrorism," he said. "I will make America safer."

The comments were made in the wake of two videotapes that were broadcast this week -- one from al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden -- threatening to unleash more terror attacks against the United States. Neither candidate mentioned the tapes in their speeches. (Full story)

Bush spent Saturday morning traveling across the Midwest and ended his campaign appearances in Orlando, Florida. He currently has a lead in the polls over Kerry. (CNN.com's Poll Tracker)

During his speeches, Bush highlighted his record as a wartime president and said a steady leader is needed in the war on terror.

"The terrorists that killed thousands of people are still dangerous and ready to strike," he said at a rally in Ashwaubenon, Wisconsin, early in the day.

He called his opponent indecisive and said Kerry lacked the resolve needed to lead the nation during a perilous time.

"Whether you agree with me or disagree with me, you know where I stand, you know what I believe," Bush said.

Bush began the day with a rally in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where he urged supporters to go to the polls Tuesday and presented his case that he was best-suited to protect Americans. (Showdown state Michigan)

"During the last 20 years in key moments of challenge and decision, Senator Kerry has chosen the path of weakness and inaction. With that record he stands in opposition not just to me but to the great tradition of the Democratic Party," Bush said.

Kerry told a crowd in Appleton that all Americans -- Republicans and Democrats -- were united in their determination to kill bin Laden and hunt down terrorists, whom he described as "barbarians."

He said Bush was wrong to divert troops from Afghanistan and rush to war in Iraq.

"I will use all of the power that we have and all of the leadership, the leadership skill that I can summon -- and that is, believe me, more than what we have today," Kerry said. "I will lead the world in fighting a smarter, more effective, tougher, more strategic war on terror, and we will make America safer."

He repeated his assertion that Bush let bin Laden escape by using Afghan forces instead of American troops against al Qaeda in Afghanistan's Tora Bora region in the fall of 2001.

The White House has disputed that contention, and the man who commanded U.S. forces in Afghanistan at the time, retired Gen. Tommy Franks, has said it "does not square with reality."

Franks, a Bush supporter, has said that U.S. special forces played an active role at Tora Bora and that intelligence at the time placed bin Laden in any of several countries.

Both candidates have appeared in Wisconsin about a dozen times since March. In 2000, then-Vice President Al Gore edged out Bush in the state by 5,708 votes.

From Wisconsin, the two campaigns diverged, returning to other states being contested by the parties.

sexta-feira, outubro 29, 2004

Michael Moore advierte la Florida

RUI FERREIRA / El Nuevo Herald

FT. LAUDERDALE

Rodeado de cuatro guardaespaldas, un centenar de admiradores y algunos activistas de la campaña del senador John Kerry, el controvertido cineasta Michael Moore hizo esta noche lo que dijo ser la primera de ''varias'' visitas a la Florida para ''supervisar'' estas elecciones presidenciales.

Foto: Rui Ferreira

''No vamos a dejar que una vez más nos roben las elecciones. Las boletas tienen que aparecer y van aparecer'', declaró Moore, en un improvisado discurso en las escaleras de la junta electoral del condado Broward, en el downtown de Ft. Lauderdale.

Moore fue recibido también por un pequeño grupo de partidarios del presidente George W. Bush, quienes acompañaron sus palabras con continuas consignas de ''cuatro años más'' y ``No a Kerry''.

''Creo que les vamos a dar cuatro días más, porque las cosas están bien aquí en la Florida sólo tenemos que dar un empujoncito más'', señaló el autor del polémico documental Fahrenheit 911.

Foto: Rui Ferreira

Moore explicó que el día de las elecciones piensa traer a su equipo cinematográfico para ''seguir de cerca'' el proceso y ``denunciar todas las irregularidades que podamos''.

La visita del cineasta coincidió con el aparente extravío de unas 60,000 boletas ausentes en el condado de Broward y una jornada de fuertes intercambios de acusaciones entre demócratas y republicanos de intentos de interferir en las votaciones adelantadas.

''Pero ustedes también pueden hacer algo. Quiero decirles que hay todo un equipo con miles de abogados voluntarios en el estado, a quienes ustedes deben llamar si no los dejan votar, porque no nos detendremos hasta que cada voto sea contado, porque todos los votos cuentan'', apuntó.

Foto: Rui Ferreira

Y, ''si les impiden votar, quiero que sepan que encontraremos a los responsables'', enfatizó Moore, sin mencionar quién lo haría o a nombre de quién estaba hablando.

Según la portavoz de la campaña demócrata, Arelys Escalera, el cineasta ``está actuando por su cuenta''.

Foto: Rui Ferreira

Moore dijo que participó en la protesta frente a la junta electoral porque ''el sistema electoral está en peligro'', pero también ``para asegurarles a ellos [los republicanos] que los vamos a tratar bien cuando a partir del 20 de enero el presidente Kerry tome posesión''.

''A partir de ese día los vamos a dejar casarse entre ellos; que cuando necesiten de salud pública la van a tener; que cuando traigamos a nuestros hijos de Irak también traeremos los de ellos y a partir del 20 de enero no los vamos a tratar como han tratado a las minorías en los últimos cuatro años'', enfatizó Moore.

(C) 2004 El Nuevo Herald

FT. LAUDERDALE

Rodeado de cuatro guardaespaldas, un centenar de admiradores y algunos activistas de la campaña del senador John Kerry, el controvertido cineasta Michael Moore hizo esta noche lo que dijo ser la primera de ''varias'' visitas a la Florida para ''supervisar'' estas elecciones presidenciales.

Foto: Rui Ferreira

''No vamos a dejar que una vez más nos roben las elecciones. Las boletas tienen que aparecer y van aparecer'', declaró Moore, en un improvisado discurso en las escaleras de la junta electoral del condado Broward, en el downtown de Ft. Lauderdale.

Moore fue recibido también por un pequeño grupo de partidarios del presidente George W. Bush, quienes acompañaron sus palabras con continuas consignas de ''cuatro años más'' y ``No a Kerry''.

''Creo que les vamos a dar cuatro días más, porque las cosas están bien aquí en la Florida sólo tenemos que dar un empujoncito más'', señaló el autor del polémico documental Fahrenheit 911.

Foto: Rui Ferreira

Moore explicó que el día de las elecciones piensa traer a su equipo cinematográfico para ''seguir de cerca'' el proceso y ``denunciar todas las irregularidades que podamos''.

La visita del cineasta coincidió con el aparente extravío de unas 60,000 boletas ausentes en el condado de Broward y una jornada de fuertes intercambios de acusaciones entre demócratas y republicanos de intentos de interferir en las votaciones adelantadas.

''Pero ustedes también pueden hacer algo. Quiero decirles que hay todo un equipo con miles de abogados voluntarios en el estado, a quienes ustedes deben llamar si no los dejan votar, porque no nos detendremos hasta que cada voto sea contado, porque todos los votos cuentan'', apuntó.

Foto: Rui Ferreira

Y, ''si les impiden votar, quiero que sepan que encontraremos a los responsables'', enfatizó Moore, sin mencionar quién lo haría o a nombre de quién estaba hablando.

Según la portavoz de la campaña demócrata, Arelys Escalera, el cineasta ``está actuando por su cuenta''.

Foto: Rui Ferreira

Moore dijo que participó en la protesta frente a la junta electoral porque ''el sistema electoral está en peligro'', pero también ``para asegurarles a ellos [los republicanos] que los vamos a tratar bien cuando a partir del 20 de enero el presidente Kerry tome posesión''.

''A partir de ese día los vamos a dejar casarse entre ellos; que cuando necesiten de salud pública la van a tener; que cuando traigamos a nuestros hijos de Irak también traeremos los de ellos y a partir del 20 de enero no los vamos a tratar como han tratado a las minorías en los últimos cuatro años'', enfatizó Moore.

(C) 2004 El Nuevo Herald

quinta-feira, outubro 28, 2004

Carta da América

quarta-feira, outubro 27, 2004

Absentee Ballots Missing in Florida County

Police Investigating as Many as 58,000 Ballots Yet to Reach Voters in Broward County

FORT LAUDERDALE, Fla. -- Up to 58,000 absentee ballots may never have reached the Broward County voters who requested them more than two weeks ago, election officials said, and state police are investigating.

Hundreds of people have called the county elections office to complain that they never got their ballots. The phone system was so overwhelmed some frustrated voters could not get through.

The county election office said the problem involved ballots mailed on Oct. 7-8, though the number of those actually missing was uncertain. Some absentee ballots mailed on those dates have already been returned to be counted.

"We are trying to determine what occurred and whether there was any kind of criminal violation," said Paige Patterson-Hughes, spokeswoman for the Florida Department of Law Enforcement.

The county blamed the U.S. Postal Service. "That is something beyond our control," Deputy Supervisor of Elections Gisela Salas said. "We really have no idea what's going on."

Postal officials said the post office was not to blame.

"We have employees that we assign to handle the absentee ballots that come in," said Enola C. Rice, a Postal Service spokeswoman in South Florida. "So all the absentee ballots that are received by the Postal Service are processed and delivered immediately."

Absentee voters who did not receive a ballot can request another, which officials said would be sent by overnight mail.

© 2004 The Associated Press

FORT LAUDERDALE, Fla. -- Up to 58,000 absentee ballots may never have reached the Broward County voters who requested them more than two weeks ago, election officials said, and state police are investigating.

Hundreds of people have called the county elections office to complain that they never got their ballots. The phone system was so overwhelmed some frustrated voters could not get through.

The county election office said the problem involved ballots mailed on Oct. 7-8, though the number of those actually missing was uncertain. Some absentee ballots mailed on those dates have already been returned to be counted.

"We are trying to determine what occurred and whether there was any kind of criminal violation," said Paige Patterson-Hughes, spokeswoman for the Florida Department of Law Enforcement.

The county blamed the U.S. Postal Service. "That is something beyond our control," Deputy Supervisor of Elections Gisela Salas said. "We really have no idea what's going on."

Postal officials said the post office was not to blame.

"We have employees that we assign to handle the absentee ballots that come in," said Enola C. Rice, a Postal Service spokeswoman in South Florida. "So all the absentee ballots that are received by the Postal Service are processed and delivered immediately."

Absentee voters who did not receive a ballot can request another, which officials said would be sent by overnight mail.

© 2004 The Associated Press

Computer Analysis Shows 33 Ways To End in a Tie

By Dana Milbank

Washington Post

Could one of these electoral college nightmares be our destiny?

President Bush and Sen. John F. Kerry deadlock on Tuesday with 269 electoral votes apiece -- but a single Bush elector in West Virginia defects, swinging the election to Kerry.

Or Bush and Kerry are headed toward an electoral college tie, but the 2nd Congressional District of Maine breaks with the rest of the state, giving its one electoral vote -- and the presidency -- to Bush.

Or the Massachusetts senator wins an upset victory in Colorado and appears headed to the White House, but a Colorado ballot initiative that passes causes four of the state's nine electoral votes to go to Bush -- creating an electoral college tie that must be resolved in the U.S. House.

None of these scenarios is likely to occur next week, but neither is any of them far-fetched. Tuesday's election will probably be decided in 11 states where polls currently show the race too tight to predict a winner. And, assuming the other states go as predicted, a computer analysis finds no fewer than 33 combinations in which those 11 states could divide to produce a 269 to 269 electoral tie.

Normally, such outcomes are strictly theoretical. But not this time, with the election seemingly so close and unpredictable. "Flukey things probably happen in every election, but because most are not close nobody pays any attention," said Charles E. Cook Jr., an elections handicapper. "But when it's virtually a tied race, hell, what isn't important?" Cook says this election is on course to match 2000's distinction of having five states decided by less than half a percentage point.

It is still possible that the vote on Tuesday will produce a clear winner of both the electoral and popular votes. But if the winner's margin is small -- less than 1 percent of the popular vote is a rule of thumb -- the odds increase that the quirks of the electoral college could again decide the presidency and again raise doubts about a president's legitimacy.

"Let us hope for a wide victory by one of the two; the alternative is too awful to contemplate," said Walter Berns, an electoral college specialist at the American Enterprise Institute.

But many political strategists are preparing for a narrow -- and possibly split -- decision. Jim Jordan, former Kerry campaign manager now working on a Democratic voter-mobilization effort, puts the odds at 1 in 3 that Bush will share the fate Al Gore suffered in 2000: a popular-vote win but an electoral loss. "It's actually looking more and more plausible," he said, citing a number of polls showing a Bush lead nationally but a Kerry lead in many battleground states.

A repeat of 2000 -- Bush losing the popular vote but winning the electoral count -- is considered less likely because the president has been boosting his support in already Republican states and reducing his deficit in some safely Democratic states.

Even without a split between the electoral and popular votes, there is room for electoral mischief. To begin with, there are the 33 scenarios under which the battleground states could line up so that Kerry and Bush are in an electoral tie. Even if only the six most fiercely contested states are considered -- Florida, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Ohio and Wisconsin -- the electoral vote would be tied if Kerry wins Florida, Minnesota and New Hampshire while Bush wins New Mexico, Ohio and Wisconsin.

Under the 12th Amendment, if one candidate does not get 270 votes, the decision goes to the House, where each state gets a vote -- a formula that would guarantee a Bush victory (the Senate picks the vice president). A House-decided election could produce even more protests than the 2000 election did. That, writes Ryan Lizza of the New Republic, who spelled out 17 scenarios under which the election could end in an electoral tie, is perhaps the only way "for a second Bush term to seem more illegitimate in the eyes of Democrats than his first term."

The possibility of a tie or near-tie in the electoral college also makes it more possible for individual electors to cause havoc. In West Virginia, one of the state's five Republican electors, South Charleston Mayor Richie Robb, has said he might not vote for Bush (although he calls it "unlikely" he would support Kerry). And in Ohio, the political publication the Hotline reports, one of Kerry's 20 electors could be disqualified because he is a congressman. Such problems and "faithless electors" have surfaced before, but the elections were not close enough for it to matter.

In Maine, the state appears to be comfortably in Kerry's column. But the state splits its electoral votes based in part on the vote in each congressional district. If Bush wins in Maine's 2nd District, where Kerry has a narrow lead, the president would take one of the state's four electoral votes, a potentially decisive difference. For example, if Bush takes New Hampshire, Ohio and Wisconsin; Kerry gets Florida, Minnesota and New Mexico; and the other 44 states follow recent polls, Kerry will win the election with 270 votes -- unless Maine's 2nd District turns against him.

Conversely, Bush is favored to win Colorado's nine electoral votes. But a ballot initiative being decided Tuesday would cause the state's electoral votes to be distributed proportionally -- almost certainly meaning five electoral votes for the winner and four for the loser. Polls show the ballot initiative is likely to fail, but if it passes, the presidential election could change with it.

If Bush were to win Colorado along with the key battlegrounds of New Hampshire, New Mexico and Ohio (and other states followed polls' predictions) he would have 273 electoral votes -- but that would become a tie at 269 votes if the ballot initiative passes. Alternatively, if Kerry were to win Colorado and claim Minnesota, New Mexico and Ohio, he would have 272 votes -- until Colorado's ballot initiative returned four votes, and the presidency, to Bush.

© 2004 The Washington Post Company Washington Post

Could one of these electoral college nightmares be our destiny?

President Bush and Sen. John F. Kerry deadlock on Tuesday with 269 electoral votes apiece -- but a single Bush elector in West Virginia defects, swinging the election to Kerry.

Or Bush and Kerry are headed toward an electoral college tie, but the 2nd Congressional District of Maine breaks with the rest of the state, giving its one electoral vote -- and the presidency -- to Bush.

Or the Massachusetts senator wins an upset victory in Colorado and appears headed to the White House, but a Colorado ballot initiative that passes causes four of the state's nine electoral votes to go to Bush -- creating an electoral college tie that must be resolved in the U.S. House.

None of these scenarios is likely to occur next week, but neither is any of them far-fetched. Tuesday's election will probably be decided in 11 states where polls currently show the race too tight to predict a winner. And, assuming the other states go as predicted, a computer analysis finds no fewer than 33 combinations in which those 11 states could divide to produce a 269 to 269 electoral tie.

Normally, such outcomes are strictly theoretical. But not this time, with the election seemingly so close and unpredictable. "Flukey things probably happen in every election, but because most are not close nobody pays any attention," said Charles E. Cook Jr., an elections handicapper. "But when it's virtually a tied race, hell, what isn't important?" Cook says this election is on course to match 2000's distinction of having five states decided by less than half a percentage point.

It is still possible that the vote on Tuesday will produce a clear winner of both the electoral and popular votes. But if the winner's margin is small -- less than 1 percent of the popular vote is a rule of thumb -- the odds increase that the quirks of the electoral college could again decide the presidency and again raise doubts about a president's legitimacy.

"Let us hope for a wide victory by one of the two; the alternative is too awful to contemplate," said Walter Berns, an electoral college specialist at the American Enterprise Institute.

But many political strategists are preparing for a narrow -- and possibly split -- decision. Jim Jordan, former Kerry campaign manager now working on a Democratic voter-mobilization effort, puts the odds at 1 in 3 that Bush will share the fate Al Gore suffered in 2000: a popular-vote win but an electoral loss. "It's actually looking more and more plausible," he said, citing a number of polls showing a Bush lead nationally but a Kerry lead in many battleground states.

A repeat of 2000 -- Bush losing the popular vote but winning the electoral count -- is considered less likely because the president has been boosting his support in already Republican states and reducing his deficit in some safely Democratic states.

Even without a split between the electoral and popular votes, there is room for electoral mischief. To begin with, there are the 33 scenarios under which the battleground states could line up so that Kerry and Bush are in an electoral tie. Even if only the six most fiercely contested states are considered -- Florida, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Ohio and Wisconsin -- the electoral vote would be tied if Kerry wins Florida, Minnesota and New Hampshire while Bush wins New Mexico, Ohio and Wisconsin.

Under the 12th Amendment, if one candidate does not get 270 votes, the decision goes to the House, where each state gets a vote -- a formula that would guarantee a Bush victory (the Senate picks the vice president). A House-decided election could produce even more protests than the 2000 election did. That, writes Ryan Lizza of the New Republic, who spelled out 17 scenarios under which the election could end in an electoral tie, is perhaps the only way "for a second Bush term to seem more illegitimate in the eyes of Democrats than his first term."

The possibility of a tie or near-tie in the electoral college also makes it more possible for individual electors to cause havoc. In West Virginia, one of the state's five Republican electors, South Charleston Mayor Richie Robb, has said he might not vote for Bush (although he calls it "unlikely" he would support Kerry). And in Ohio, the political publication the Hotline reports, one of Kerry's 20 electors could be disqualified because he is a congressman. Such problems and "faithless electors" have surfaced before, but the elections were not close enough for it to matter.

In Maine, the state appears to be comfortably in Kerry's column. But the state splits its electoral votes based in part on the vote in each congressional district. If Bush wins in Maine's 2nd District, where Kerry has a narrow lead, the president would take one of the state's four electoral votes, a potentially decisive difference. For example, if Bush takes New Hampshire, Ohio and Wisconsin; Kerry gets Florida, Minnesota and New Mexico; and the other 44 states follow recent polls, Kerry will win the election with 270 votes -- unless Maine's 2nd District turns against him.

Conversely, Bush is favored to win Colorado's nine electoral votes. But a ballot initiative being decided Tuesday would cause the state's electoral votes to be distributed proportionally -- almost certainly meaning five electoral votes for the winner and four for the loser. Polls show the ballot initiative is likely to fail, but if it passes, the presidential election could change with it.

If Bush were to win Colorado along with the key battlegrounds of New Hampshire, New Mexico and Ohio (and other states followed polls' predictions) he would have 273 electoral votes -- but that would become a tie at 269 votes if the ballot initiative passes. Alternatively, if Kerry were to win Colorado and claim Minnesota, New Mexico and Ohio, he would have 272 votes -- until Colorado's ballot initiative returned four votes, and the presidency, to Bush.

terça-feira, outubro 26, 2004

Carta da América

Daqui a uma semana temos presidente. Ou não!

Daqui a uma semana temos presidente. Ou não!

Tudo depende de se o eleitorado comprou a mensagem chave desta campanha: é Bush a unica pessoa capaz de enfrentar o terrorismo? Ou Kerry também está à altura dos acontecimentos e pode recuperar o prestigio americano no mundo.

As sondagens pouco dizem, os dois estão empatados, mas no meio disto tudo o Bill Clinton é capaz de ter razão

De passagem por Miami ontem à noite, Clinton disse-me que esperava ver os democratas ganhar, mas admitiu que tudo depende de quem vai votar; depende da quantidad de seguidores que os dois partidos possam mobilizar.

Ora isto foi exactamente o que aconteceu há quatro anos, os partidos atiraram para a rua mais 60 por cento de eleitores que o que era habitual, e a máquina eleitoral rebentou. Foi o caos. Os Americanos demoraram 50 dias em apurar um presidente. E este ano a campanha é tão emocional que poderia contecer o mesmo. Ouça aqui.

Rui Ferreira

La guerra de los cristeros

por ALEJANDRO ARMENGOL

Mal anda la campaña por la presidencia de Estados Unidos, cuando ambos candidatos apelan cada vez más en sus discursos a los sentimientos religiosos de los electores. En el presidente George W. Bush es natural este llamado a la fe, ya que desde la llegada al poder se ha considerado un “mensajero de Dios”. Pero en su oponente, el senador John Kerry, implica una táctica de última hora que suena a desesperación ante la imposibilidad de cobrar la delantera en los días finales antes del momento cumbre, cuando los norteamericanos decidirán en las urnas el futuro de la nación y de gran parte de lo que lo que ocurra en el mundo durante los próximos cuatro años.

De acuerdo a las cifras, Kerry lleva las de perder en este terreno.

Aproximadamente el 42 por ciento de los habitantes de EEUU se consideran evangélicos o “nacidos de nuevo” —la autodenominada forma de clasificarse que caracteriza a los que como Bush dicen haber “encontrado al Señor”— quienes practican una religión cristiana, dividida en múltiples iglesias y sectas, aunque todas con el denominador común de una práctica religiosa protestante. Hay también unos cuatro millones de evangélicos que no votaron en noviembre de 2000, nuevos electores cuya amplia mayoría posiblemente se incline hacia el Presidente. Kerry, por su parte, profesa la religión católica, aunque su posición antidogmática respecto al aborto, la investigación con células madre y los matrimonios homosexuales le ha ganado la oposición de destacadas figuras de la institución católica en este país.

Desde su llegada al poder, Bush ha hecho del fundamentalismo cristiano la coraza ideológica que rige sus acciones. Incluso en varias ocasiones ha empleado el término “cruzada” para referirse a su guerra contra el terrorismo, lo que ha provocado siempre la necesidad de desmentidos y aclaraciones —por parte de sus voceros y funcionarios— para no aumentar aún más las tensiones con los musulmanes del país y el resto del mundo. Al tiempo que este alarde de fe es una de las características más notorias —y criticada— de la personalidad del mandatario, su apoyo sostenido a la causa cristiana ha sido uno de los pilares electorales que mayores dividendos le ha brindado. En la actual campaña, las iglesias han actuado como centros de reclutamiento de votantes, los pastores han urgido a sus feligreses que voten por Bush y multitud de fieles han expresado la creencia de que “Dios está usando al Presidente en su lucha contra el Maligno”. Según una encuesta luego de las elecciones de 2000, realizada por la Universidad de Akron, más de dos tercios los que dijeron asistir al menos una vez por semana a la iglesia votaron por Bush. No quiere esto decir que todos los cristianos sean ciegos abanderados del actual presidente, pero nunca como ahora —en la historia reciente de EEUU— la religión ha jugado un papel tan clave en las decisiones ante las urnas.

Kerry ha intensificado las referencias bíblicas en sus últimos discursos con el afán de ganarse a los votantes indecisos, quienes continúan siendo la gran incógnita electoral. Una táctica política válida que no impide la sospecha de que, una vez más, se coloque a la defensiva y haga el papel de caja de resonancia —en un sentido opuesto— frente a las propuestas de Bush.

El fundamentalismo cristiano tiene claro lo mucho que puede ganar si el Presidente es reelecto. Bush les ha ofrecido mayores recursos económicos a las instituciones benéficas de las iglesias y sectas, la continuación de la prohibición de fondos federales para las investigaciones con células madre y el proseguir la erosión de la distinción primordial entre Iglesia y Estado. Pero lo más importante es la certeza de que un segundo mandato de Bush implicará la nominación de uno o más magistrados a la Corte Suprema. Estas nominaciones constituyen una prioridad presidencial, e incluso sin el apoyo del Congreso —en la actualidad ambas cámaras están en manos de los republicanos— no quedaría otra opción que aceptar a jueces conservadores. De esta forma, se rompería el precario equilibrio existente en el Supremo, y éste se inclinaría irremediablemente a la derecha, con la posibilidad de que el aborto sea prohibido o limitado a los casos extremos.

Hasta ahora, Kerry se había mostrado como un católico moderado, que prefería mantener en el terreno privado sus convicciones religiosas. Durante la elecciones primarias de su partido, se mostró renuente a discutir cuestiones religiosas y destacó el peligro que representaba el intento de Bush de borrar la distancia entre Iglesia y Estado. Todo cambió durante el último debate televisivo, en que expresó: “Mi fe afecta todo lo que hago”. La declaración guarda similitudes con lo que viene expresando desde hace años Bush, incluso al referirse a las decisiones claves de su mandato. En Plan of Attack, el Presidente le confesó a Bob Woodward respecto a su decisión de lanzar la invasión a Irak: “Llegado a este punto, comencé a orar, a fin de tener la fortaleza necesaria para hacer la voluntad del Señor. …Téngalo por seguro, no voy a justificar una guerra fundamentándome en Dios. No obstante, en mi caso, oré para ser tan buen mensajero de su voluntad como fuera posible. Y entonces, por supuesto, oré por fortaleza personal e indulgencia”. Más allá de las semejanzas de los dos candidatos, en declararse hombres de fe, las diferencias son abismales. Kerry es un político práctico, que a lo largo de su carrera nunca ha puesto a los hechos por encima de sus creencias. Bush es un fanático —al estilo calvinista— que subordina la realidad a su ideología. Este fervor dogmático comenzó a acentuarse luego de los ataques terroristas del 9/11. A partir de ese momento, la actual administración acentuó un estilo de gobierno que exige la lealtad absoluta a sus seguidores, el secreto absoluto respecto a su gestión y la desconfianza total frente a cualquiera que presente un punto de vista contrario o aparezca con una información que ponga en entredicho los planes formulados.

Durante toda la campaña, las distinciones entre los aspirantes a la presidencia han estado centradas siempre en las diferencias de carácter, interpretadas como positivas o negativas de acuerdo a la militancia política de quien las contemple: Bush testarudo y Kerry analítico y dispuesto a reconocer sus errores; Bush firme y Kerry pusilánime y cambiante.

Estas diferencias, sin embargo, trascienden las personalidades. El gobierno de Bush tiene un marcado afán imperialista y una forma autoritaria, que sin duda se profundizará en caso de una victoria. No son sólo las grandes lagunas del mandatario respecto a lo que ocurre fuera de la Casa Blanca y sus limitaciones intelectuales. Tampoco su desprecio ante la opinión ajena y la renuencia a escuchar consejos hasta de sus más cercanos colaboradores, una actitud tan bien expresada por el ex secretario del Tesoro, Paul O’Neill, cuando dijo que en las reuniones de gabinete Bush se comportaba como “un ciego en una habitación llena de sordos”. EEUU está en manos de un grupo de ideólogos que pertenecen al ala ultraderechista de nuevo cuño del Partido Republicano, los llamados “neoconservadores”, quienes responden a los intereses de las corporaciones y la industria armamentista y reflejan los valores del fundamentalismo cristiano de los estados sureños. Para mantener su hegemonía, no dudarán ni por un momento lanzarse a una nueva guerra, harán todo lo posible por destruir el sistema de seguridad social y ampliarán todas las políticas que impliquen un aumento de las ganancias de los grupos más poderosos, en detrimento de las clases medias y bajas de la población.

Como ha ocurrido en otras ocasiones, el énfasis religioso que ha adquirido la campaña no hace más que ocultar la situación imperante en EEUU. Es cierto que, desde el punto de vista religioso, el enfoque pragmático de Kerry es más acorde al catolicismo, mientras que el irracionalismo de Bush encaja a las claras en el protestantismo. Pero esta nación se caracteriza por el establecimiento de vínculos políticos que trascienden las barreras del credo. ¿Cómo explicar entonces la alianza entre los fundamentalistas cristianos y el sionismo? La respuesta es fácil: ambos grupos han echado a un lado sus diferencias de fe en favor de un gobierno norteamericano que no pone freno a los desmanes del aventurerismo militar de Ariel Sharon. Al final, la victoria la tendrá el candidato que logre convencer o engañar mejor a los votantes. Para lograrlo Bush ora y Kerry reza, pero sus asesores saben que no basta con las oraciones.

(C) AA 2004

segunda-feira, outubro 25, 2004

Carta da América

Teresa Simões Ferreira, mais conhecida por Teresa Heinz Kerry não se deixa calar. Há cinco dias que os colegas do marido, o senador John Kerry, não a deixavam falar em público desde que disse que Laura Bush, bibliotecaria antes de ir para a Casa Branca, não tinha profissão conhecida.

Teresa Simões Ferreira, mais conhecida por Teresa Heinz Kerry não se deixa calar. Há cinco dias que os colegas do marido, o senador John Kerry, não a deixavam falar em público desde que disse que Laura Bush, bibliotecaria antes de ir para a Casa Branca, não tinha profissão conhecida.

Hoje de manhã, Teresa admitiu-me que foi um engano involuntario mas que nem por isso a vão calar. O problema não é novo. O sangue lusitano de Heinz Kerry já causou alguns embarços ao marido e o pessoal de campanha entra literalmente em panico cada vez que ela abre a boca.

Mas esta manha não esteve pelos ajustes. Não façam casos aos politicos, lutem e exijam os vossos direitos e reclamem cada vez que les mintam, disse a Teresa à minha frente a um grupo de inmigrantees mexicanos. Os olhares dos seus conselheiros foram um poema, habituados como esrtão a nem sempre dizer a verdade. É possivel que nos próximos dias decidam mante-la calada. Ouça aqui.

Rui Ferreira

sexta-feira, outubro 22, 2004

Nos ultimos dias Bush e Kerry andam com uma preocupação impressionante. Querem que o eleitorado tenha a certeza que acreditam em Deus e se são elleitos a relação do estado com a igreja não muda e em todas as moedas continuará escrito em Deus confiamos e nas notas continuarão a ter esse enorme olho aberto e maçonico que pareçe olhar para tudo e todos.

Nos ultimos dias Bush e Kerry andam com uma preocupação impressionante. Querem que o eleitorado tenha a certeza que acreditam em Deus e se são elleitos a relação do estado com a igreja não muda e em todas as moedas continuará escrito em Deus confiamos e nas notas continuarão a ter esse enorme olho aberto e maçonico que pareçe olhar para tudo e todos.

Mas o que ambos não gostam, é de que se fale até que ponto o misticismo joga um a papel nas suas vidas. Em tempos recentes tornaram-se conhecidas as idas à bruxa de Nancy Reagan na véspera de alguma decisão importante do marido. O propio George Bush admitiu que consultou o mais além antes de invadir o Iraq. Portanto, neste sentido já sabemos o que a casa gasta.

A grande incógnita é John Kerry. Dizem que na sede da campanha há muitas velinhas acesas. Não para que ele seja eleito mas sim para ver se conseguem emprego no mes que vem porque com as sondagens a virem por aí abaixo em duas semanas podem estar todos desempregados. Já é uma pista, não é? Ouça aqui.

Rui Ferreira

quinta-feira, outubro 21, 2004

La guerra graciosa y la dictadura simpática

por Zoe Valdés

Los escritores, igual que cualquier otro ser humano razonable, en principio estamos en contra de la guerra, de cualquier guerra.Estoy y estuve en contra de la guerra, primero que nada por las consecuencias espantosas que engendra y después porque me siento harta, aburrida y hasta avergonzada, con vergüenza ajena, de aquellos escritores y artistas que como papagayos oportunistas, para ganarse puntos con el poder, no paran de cacarear que están en contra de la Guerra de Irak, que escriben en contra de la Guerra de Irak, entonces, sólo para que se termine de una vez el tema de la guerra, hay que acabar con la guerra. No niego que cuando vi caer las estatuas de Sadam Husein me sentí inmensamente feliz y aún más cuando cayó el propio dictador, legañoso y miedoso en su madriguera. Bien, pero, ¿en contra de qué guerra están algunos intelectuales y artistas e incluso políticos? ¿Por qué sólo están en contra de la guerra en Irak? Ah, porque es, según ellos, una guerra de oligarcas y por ahí se sueltan en disertaciones espumeantes de cava.

¿Por qué no enfrentan su airada escritura en contra de otras guerras? ¿Por qué no ponen sus palabras en contra de la guerra que desató Osama bin Laden el 11-S en Nueva York? ¿Por qué no están en contra de la guerra desatada contra los ciudadanos españoles el 11-M? ¿Por qué no están en contra de la guerra en un continente que les interesaría y que les debería tocar más de cerca, como es el continente americano? ¿Por qué, en fin, no se manifiestan en contra de la guerra de guerrillas perpetrada desde hace casi medio siglo por el Ché y Fidel Castro? ¿Desconocen acaso la cantidad de víctimas que ha amontonado la sanguinaria guerra de narcoguerrilleros colombianos? Por mucho que me lo expliquen, no entiendo la inercia para algunas cosas y la inmovilidad para otras.

Pero en ese tema manido y manipulado no brillan sólo los escritores y artistas. En los famosos debates de George W. Bush y de John Kerry, no ha habido otro careo con sustancia internacional más contundente que el de la Guerra de Irak, teniendo al lado la peligrosísima infección de la guerrilla colombiana, una guerra sin cuartel contra inocentes, con fronteras con Venezuela, país que bajo el dominio absoluto del caudillo Hugo Chávez (y de Fidel Castro), el loco que ha dado albergue a ETA, el íntimo amigo del terrorista Carlos. ¿Cómo obviar el horror en nombre de la izquierda que desde hace años se gesta en América Latina, en materia de terrorismo internacional, incluyendo a miembros del IRA y a grupos islamistas árabes?

Fidel Castro lo afirmó, muy al inicio, en los años 70, lanzando de este modo, más que una advertencia, una amenaza al mundo: «Si nos propusiéramos ser terroristas, seríamos excelentes terroristas».Lo que no ha cesado de ocurrir. No olvidar que bajo las órdenes del Comandante Piñeyro, más conocido como Barbarroja, se creó en el Departamento América del Consejo de Estado Castrista, una célula terrorista que secuestraba, chantajeaba y asesinaba a banqueros italianos, a familias que se veían obligadas a pagar el impuesto revolucionario. ¿Les recuerda esto algo a los españoles? Además, qué raro que contra la guerra desatada por ETA se pronuncien tan poco la mayoría de los escritores y artistas españoles, que incluso con su voto han apoyado a políticos que arengan a los etarras a atentar contra otros sitios de España que no sean Cataluña.La vergüenza, como dirían los franceses.

O sea que, por lo que vemos, salvo la Guerra de Irak, todas las demás guerras parecería que fueran graciosas para algunos, gozan de gran simpatía en el núcleo de la intelectualidad y de los medios artísticos de la izquierda internacional, sobre todo de la española. Lo que constituye más que una ofensa una colaboración directa, una complicidad alevosa y excesivamente dañina, que no respeta lo principal, el derecho a la vida. Por culpa de estos tontos útiles algo mucho más trágico podría suceder, porque el día menos pensado, seremos capaces de aceptar como normal que un grupo terrorista nos haga picadillo con un collar de explosivos anudado al cuello como rutina. Sepan que ya le ocurrió a una colombiana, quien era solamente una maestra de pueblo. Aunque en estos horrores no existen distinciones que valgan. Si seguimos como vamos, el terrorismo destruirá los logros de la democracia.Ya vivimos un antecedente el 11-M en Madrid, ¿cómo han podido olvidarlo los intelectuales españoles? Indiscutiblemente, vuelvo y reitero, para cierta gente hay guerras graciosas y dictaduras simpáticas, a las que apoyan, y hasta ahora son las que más víctimas inocentes se han cobrado.

Después hay otro tipo de colaboración siniestra. La de los gobiernos de izquierda. Acabo de leer una carta de Vladimiro Roca, presidente de Todos Unidos y de los socialdemócratas cubanos, por supuesto, en la disidencia, hijo del antiguo luchador comunista Blas Roca.Vladimiro Roca se dirige al presidente Rodríguez Zapatero explicándole con puntos muy claros su posición política en la disidencia interna, su marcado deseo de diálogo, y subraya que no puede haber diálogo con quien no está dispuesto a escuchar opiniones diferentes.Más claro ni el agua y, declara Vladimiro Roca, (sería bueno que esta carta fuera publicada en algún diario español) que no comprende la posición del Gobierno de Rodríguez Zapatero en relación a la UE y Cuba, que tiene una «brillante actuación diplomática» (entrecomillado mío) en el incidente de la embajada española, el Día de la Hispanidad, mediante el portento verborreico del embajador Zaldívar, quien ofendió crudamente a los disidentes que se hallaban en la sede diplomática, invitados por él mismo, sin duda alguna. Algo que sólo podemos asimilar los que conocemos la «sutileza ibérica» (entrecomillado mío). Impensable en los medios diplomáticos galos, invitar a alguien para después agredirlo verbalmente, humillarlo y además amenazarlo. Peor si tenemos en cuenta que estos disidentes se mueven con cero posibilidades políticas dentro de su propio país, yo diría que sólo han tenido esa posibilidad cuando las embajadas los han invitado, ha sido cuando han podido ser escuchados en ambientes democráticos.Y aún peor, si no ignoramos que entre ellos se encontraba el dirigente Osvaldo Payá Sardiñas, Premio Sajarov por los derechos humanos, a quien más de 24.000 firmas cubanas, ya no clandestinas, han respaldado su Proyecto Varela. Y la reconocida disidente y economista Marta Beatriz Roque, presa en dos ocasiones, perenne luchadora por los derechos cubanos, coautora del documento La patria es de todos. Todavía ninguna ministra feminista del actual Gobierno de Zapatero ni ninguna escritora y artista de las del ¡Pásalo! se han dignado a mencionar a esta mujer ni a añadirla a su larga lista de ejemplares luchadoras por la paz y por la democracia. Ya me gustaría ver a la señora Leire Pajín, a quien acabo de ver en la televisión declarando que si la transición pacífica en Cuba, que si el diálogo. Señora Pajín, ¿cree usted que hubiera podido haber diálogo con Pinochet, con Hitler? Señora Pajín, es usted mujer, ¿no le da vergüenza dialogar con una dictadura en lugar de escuchar y dialogar con Marta Beatriz Roque o con las Damas de Blanco, el equivalente de las madres de la Plaza de Mayo? Señora Pajín, creo que usted no sabe ni de lo que habla ni conoce a las Damas de Blanco ni se preocupa por Marta Beatriz Roque. Creo que usted está puesta de bonito para repetir lo que le mandan y esperar a vestirse de maniquí a ver si le dan un chance en el próximo reportaje de revista de modas.

Para colmo, Castro se permite negar la entrada de Jorge Moragas y de un grupo de diputados holandeses, con insultos y tutti quanti.La conducta de Castro con este episodio me recuerda los múltiples momentos en que Estados Unidos ha querido levantar el embargo.La respuesta por parte de Castro siempre ha sido la misma: apretar la tuerca impidiendo de ese modo que Estados Unidos levante el embargo. Señor Rodríguez Zapatero, Castro está respondiéndole a su buena fe, en el caso de que la hubiera, como responde a los americanos.

¿Qué intelectuales de la izquierda española han firmado la reciente carta dirigida a Rodríguez Zapatero pidiéndole su apoyo en la liberación de un poeta preso? Raúl Rivero, poeta de izquierdas, enfermo, hundido en una celda llena de excrementos, de agua sucia, de ratas, de ranas, con un carcelero que lo tortura psicológicamente, de nombre Alexéi. ¿Qué pasa, por qué no se mueven? Algunos hasta han dicho que se trata de un enemigo de la revolución pagado por el imperio, ya esto lo he aclarado en varios artículos, no merece la pena que llueva sobre mojado. Hago excepción de Rosa Montero, Antonio Muñoz Molina, Fernando Savater, Juancho Armas Marcelo, pero sólo unos contados con los dedos.

Por suerte, en Francia no sucede igual y los intelectuales toman partido por los disidentes. Jorge Semprún, Jeannine Verdés-Leroux, François Masperó, Jean-Fraçois Revel, Bernard Henri-Lévy, André Glucksmann, Jean Daniel, Régis Débray, Elizabeth Burgos, Laure Adler, Jean-François Fogel, Bertrand Rosenthal, Corinne Cumerlato, Dennis Rousseau, Catherine David, Thierry Ardisson, Robert Ménard, Roman Goupil, Marek Alter, Pierre Bergé, entre otros muchos.Se ha reeditado la Carta Abierta a Fidel Castro de Fernando Arrabal, una figura excepcional de las letras españolas y galas. En uno de sus párrafos, Arrabal comenta con lujo de detalles cómo desde hace décadas los niños y jóvenes cubanos hemos tenido y tienen aún que trabajar la tierra para pagar sus estudios y las milicias de tropas territoriales, afiliarse a organizaciones castristas para ser aceptados como seres humanos. Arrabal señala que esto está prohibido en España, o sea obligar a trabajar a menores de 18 años para el beneficio del Estado y del Ejército, en condiciones de campo de concentración. Bien, pocos reparan en eso, poquísimos se suman a la protesta del poeta. El enfrentamiento a Castro, en España, es aún tímido, demasiado.

Insisto en el hecho de que contados fueron los que en su momento protestaron contra Sadam Husein cuando éste desorejaba y asesinaba a inocentes por el simple hecho de que no aprobaban su psicosis de poder, dictatorial y criminal. Pocos protestaron, y más, algunos añaden que al dictador iraquí lo pusieron los americanos, lo cual es una verdad o una falsedad a medias. Si estudiamos la Historia de Cuba, veremos cómo también, entonces, a Fidel Castro, lo puso un sector importante del Gobierno americano, de trogloditas petroleros y de mafiosos. A quienes conviene, cualquiera que sea el Gobierno, que continúe en el poder. No pienso que habrá una invasión a Cuba. Por supuesto que no la deseo, contrario a los rumores que me llegan desde Italia, de cierta gentuza que asegura haber leído, no sé dónde, que yo he apoyado la guerra en Irak y que he sugerido lo mismo para Cuba. Calumnias que no admitiré; sin embargo, espero que los intelectuales, artistas y políticos de izquierda, apoyen a la disidencia cubana ,y desde luego, se manifiesten contra otras guerras: la guerra de guerrillas y el terrorismo. Antes de que sea fatalmente tarde.

Candidates Hit Crucial Swing States of Ohio and Pennsylvania

By MARIA NEWMAN

The New York Times

President Bush asserted today that Senator John Kerry's health care plan would amount to "the largest expansion of government health care in American history,'' while the widow of Christopher Reeve announced that she had decided to speak out for Mr. Kerry because he supports embryonic stem cell research that promises progress on intractable health problems.

As the campaigns count down to the Nov. 2 presidential election, Mr. Bush and Mr. Kerry spent the day in swing states, pounding away at some of the shorthand themes that each candidate believes will win over undecided voters or hold on to his base: Mr. Bush tried to paint Mr. Kerry as a proponent of big government out of step with mainstream America, while his opponent said the president had "an extreme political agenda that slows instead of advances science.''

The president's address to an invited audience in Downingtown, Pa., was billed as being about medical liability reform. But Mr. Bush managed to weave in his refrain that Mr. Kerry's health plan would lead to higher costs and more federal involvement, a charge the Kerry campaign rejects.

"The federal government's going to become like an insurance company, a reinsurer, which sounds fine on the surface, except remember this, when the federal government writes the check, the federal government also writes the rules,'' Mr. Bush said.

The president said that in his second term, he wanted to make health care more affordable and accessible, while preserving the system of private care in this country. He also said he wanted to help families and individuals afford health insurance by setting up health savings accounts.

He said that Mr. Kerry's health care plan would add 22 million more Americans to the government system, and that he would make Medicaid a program so large that employers would be moved to drop private coverage.

But Mr. Bush did not mention that the Medicare law he signed would, by the administration's own estimate, move nine million more people into Medicare H.M.O.'s and other managed-care plans.

Also, during the last four years, the number of uninsured Americans increased by five million. Last month, the Department of Health and Human Services announced that Medicare premiums would increase in January by 17 percent.

The president said Mr. Kerry had voted 10 times as a senator against reforms in the area of medical liability. He said there were too many "junk lawsuits'' against doctors.

"We want our doctors focused on fighting illness, not on having to fight lawsuits,'' he said.

The Bush campaign wants to limit medical malpractice awards to save $60 billion to $108 billion annually in health care costs. The Kerry campaign favors limits on medical malpractice premium increases, sanctions for frivolous lawsuits, and nonbinding mediation in all states.

At a news conference arranged to coincide with President Bush's 40th visit to Pennsylvania, Gov. Ed Rendell , a Democrat, said Mr. Bush was raising the malpractice issue to distract attention from increasing numbers of people losing health care coverage and the rising costs of coverage.

"This is a typical response by the president's campaign, taking a problem that exists but is on its way to being solved by other people and blowing it up in an effort to scare the voters," Mr. Rendell said, according to The Associated Press.

Mr. Kerry, speaking in Columbus, Ohio, said the president's limits on embryonic stem cell research puts him at odds with most Americans, who believe such research should be encouraged and unhindered.

"You get the feeling that if George Bush had been president during other periods in American history, he would have sided with the candle lobby against electricity, the buggymakers against cars and typewriter companies against computers,'' Mr. Kerry said.

Mr. Kerry was introduced by Dana Reeve, whose husband, Christopher, an actor, gained fame both as "Superman'' and as a forceful advocate for spinal cord research after a fall from a horse left him a quadriplegic nine years ago. Perhaps the foremost cause for Mr. Reeve, who died on Oct. 10, was the loosening of restrictions on stem cell research.

Mr. Reeve and Mr. Kerry knew each other for about 15 years, and the actor supported Mr. Kerry's positions on stem cell research.

"My inclination would be to remain private for a good long while," Mrs. Reeve said today, her voice sometimes breaking with emotion. "But I came here today in support of John Kerry because this is so important. This is what Chris wanted.''

She said her husband had spent much of his time researching the latest scientific advances and encouraging such research to find cures for illnesses.

"He was tireless,'' she said. "He talked to researchers almost every day. He challenged scientists to move from the lab to the patient.

"Most importantly, he joined the majority of Americans in believing that the promise of embryonic stem cell research is the key to unlocking life-saving treatments and cures,'' she said to loud and sustained applause.

Mr. Kerry began the day by going hunting, emerging from an Ohio cornfield wearing camouflage gear and carrying a 12-gauge shotgun. One of the several men with him carried a goose that the senator said he had shot.

Mr. Kerry made only brief remarks, saying he had stayed up late to watch the Boston Red Sox defeat the New York Yankees last night to clinch the American League pennant.

"I'm still giddy over the Red Sox,'' Mr. Kerry said to reporters at the field, according to The Associated Press. "It was hard to focus.''

Mr. Kerry, whose home base is Boston, had joined campaign aides and other supporters to cheer his team to victory. He then woke up early for the 7 a.m. hunting event at a supporter's farm.

In the meantime, the National Rifle Association bought a full-page ad in today's Youngstown newspaper, The Vindicator, saying Mr. Kerry was posing as a sportsman while opposing gun-owners' rights. The organization, which claims four million members, endorsed Mr. Bush last week. Mr. Kerry disputes the N.R.A.'s contention that he wants to "take away" guns, although he did support the ban on assault-type weapons and legislation requiring background checks at gun shows.

"If John Kerry thinks the Second Amendment is about photo ops, he's Daffy," the ad said.

The New York Times

President Bush asserted today that Senator John Kerry's health care plan would amount to "the largest expansion of government health care in American history,'' while the widow of Christopher Reeve announced that she had decided to speak out for Mr. Kerry because he supports embryonic stem cell research that promises progress on intractable health problems.

As the campaigns count down to the Nov. 2 presidential election, Mr. Bush and Mr. Kerry spent the day in swing states, pounding away at some of the shorthand themes that each candidate believes will win over undecided voters or hold on to his base: Mr. Bush tried to paint Mr. Kerry as a proponent of big government out of step with mainstream America, while his opponent said the president had "an extreme political agenda that slows instead of advances science.''

The president's address to an invited audience in Downingtown, Pa., was billed as being about medical liability reform. But Mr. Bush managed to weave in his refrain that Mr. Kerry's health plan would lead to higher costs and more federal involvement, a charge the Kerry campaign rejects.

"The federal government's going to become like an insurance company, a reinsurer, which sounds fine on the surface, except remember this, when the federal government writes the check, the federal government also writes the rules,'' Mr. Bush said.

The president said that in his second term, he wanted to make health care more affordable and accessible, while preserving the system of private care in this country. He also said he wanted to help families and individuals afford health insurance by setting up health savings accounts.

He said that Mr. Kerry's health care plan would add 22 million more Americans to the government system, and that he would make Medicaid a program so large that employers would be moved to drop private coverage.

But Mr. Bush did not mention that the Medicare law he signed would, by the administration's own estimate, move nine million more people into Medicare H.M.O.'s and other managed-care plans.

Also, during the last four years, the number of uninsured Americans increased by five million. Last month, the Department of Health and Human Services announced that Medicare premiums would increase in January by 17 percent.

The president said Mr. Kerry had voted 10 times as a senator against reforms in the area of medical liability. He said there were too many "junk lawsuits'' against doctors.

"We want our doctors focused on fighting illness, not on having to fight lawsuits,'' he said.

The Bush campaign wants to limit medical malpractice awards to save $60 billion to $108 billion annually in health care costs. The Kerry campaign favors limits on medical malpractice premium increases, sanctions for frivolous lawsuits, and nonbinding mediation in all states.

At a news conference arranged to coincide with President Bush's 40th visit to Pennsylvania, Gov. Ed Rendell , a Democrat, said Mr. Bush was raising the malpractice issue to distract attention from increasing numbers of people losing health care coverage and the rising costs of coverage.

"This is a typical response by the president's campaign, taking a problem that exists but is on its way to being solved by other people and blowing it up in an effort to scare the voters," Mr. Rendell said, according to The Associated Press.

Mr. Kerry, speaking in Columbus, Ohio, said the president's limits on embryonic stem cell research puts him at odds with most Americans, who believe such research should be encouraged and unhindered.

"You get the feeling that if George Bush had been president during other periods in American history, he would have sided with the candle lobby against electricity, the buggymakers against cars and typewriter companies against computers,'' Mr. Kerry said.

Mr. Kerry was introduced by Dana Reeve, whose husband, Christopher, an actor, gained fame both as "Superman'' and as a forceful advocate for spinal cord research after a fall from a horse left him a quadriplegic nine years ago. Perhaps the foremost cause for Mr. Reeve, who died on Oct. 10, was the loosening of restrictions on stem cell research.

Mr. Reeve and Mr. Kerry knew each other for about 15 years, and the actor supported Mr. Kerry's positions on stem cell research.

"My inclination would be to remain private for a good long while," Mrs. Reeve said today, her voice sometimes breaking with emotion. "But I came here today in support of John Kerry because this is so important. This is what Chris wanted.''

She said her husband had spent much of his time researching the latest scientific advances and encouraging such research to find cures for illnesses.

"He was tireless,'' she said. "He talked to researchers almost every day. He challenged scientists to move from the lab to the patient.

"Most importantly, he joined the majority of Americans in believing that the promise of embryonic stem cell research is the key to unlocking life-saving treatments and cures,'' she said to loud and sustained applause.

Mr. Kerry began the day by going hunting, emerging from an Ohio cornfield wearing camouflage gear and carrying a 12-gauge shotgun. One of the several men with him carried a goose that the senator said he had shot.

Mr. Kerry made only brief remarks, saying he had stayed up late to watch the Boston Red Sox defeat the New York Yankees last night to clinch the American League pennant.

"I'm still giddy over the Red Sox,'' Mr. Kerry said to reporters at the field, according to The Associated Press. "It was hard to focus.''

Mr. Kerry, whose home base is Boston, had joined campaign aides and other supporters to cheer his team to victory. He then woke up early for the 7 a.m. hunting event at a supporter's farm.

In the meantime, the National Rifle Association bought a full-page ad in today's Youngstown newspaper, The Vindicator, saying Mr. Kerry was posing as a sportsman while opposing gun-owners' rights. The organization, which claims four million members, endorsed Mr. Bush last week. Mr. Kerry disputes the N.R.A.'s contention that he wants to "take away" guns, although he did support the ban on assault-type weapons and legislation requiring background checks at gun shows.

"If John Kerry thinks the Second Amendment is about photo ops, he's Daffy," the ad said.

Filántropo Soros lanza feroz ataque contra Bush

RUI FERREIRA / El Nuevo Herald

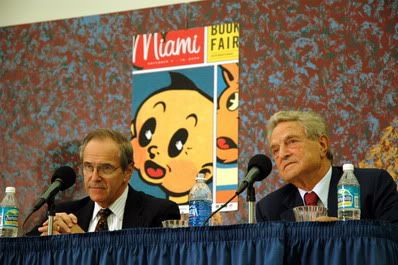

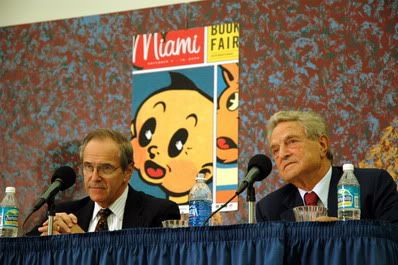

El empresario y filántropo George Soros lanzó ayer en Miami un feroz ataque al presidente George W. Bush, al cual acusó de intentar suprimir toda disidencia en Estados Unidos tras los ataques del 11 de septiembre.

''Cuando Bush fue electo, me di cuenta que los valores del país tenían que ser defendidos, pero más aún tras el 11 de septiembre, cuando el presidente silenció toda crítica con la disculpa del antipatriotismo'', dijo el empresario estadounidense, de origen húngaro.

Foto: Rui Ferreira

En su opinión, presentada ante unas 500 personas en el Miami Dade College en el marco de la Feria Internacional del Libro, Soros dijo que ''la campaña de Bush está saboteando la fundamentación de una sociedad libre'', porque ``admitir que se está equivocado es la fundamentación de una sociedad abierta''.

''Después del 11 de septiembre el presidente ha tratado de suprimir todo signo de disensión'', enfatizó.

Soros, quien abogó directamente por la elección del senador demócrata John Kerry, dijo que el presidente sabía que no había ninguna conexión entre Osama Bin Laden y Saddam Hussein, pero aun así invadió a Irak.

''¿Se imaginan lo que piensa el mundo de nosotros cuando escucha decir cosas como que no importa lo que se hace en Irak con tanto que vivamos seguros aquí?'', afirmó.

Pero, ``la verdad es que al violar la ley internacional, el presidente Bush no nos ha hecho más seguros''.

''Toda mi experiencia en democracia me dice que no se puede imponer la democracia por la violencia, e Irak sería el último lugar donde se me ocurriría experimentar con la implantación de la democracia'', añadió.

Soros estimó que la guerra en Irak ``ha hecho mucho daño a Estados Unidos, a nuestra sociedad, pero también a la moral de las tropas, porque no han sido entrenadas como una fuerza de ocupación''.

El empresario y autor de varios libros ha desarrollado una fuerte campaña contra el presidente en los últimos meses.

Foto: Rui Ferreira

Ayer, Soros no negó que quiere ver al presidente fuera de la Casa Blanca.

''Esta no es una elección normal, sino un referendo al mandato del presidente. Si lo reelegimos, no sólo estamos respaldando sus políticas, estamos asumiendo sus consecuencias'', dijo. Es más, ``rechacemos sus políticas, porque sólo así tendremos más apoyo en el mundo''.

(C) 2004 El Nuevo Herald

El empresario y filántropo George Soros lanzó ayer en Miami un feroz ataque al presidente George W. Bush, al cual acusó de intentar suprimir toda disidencia en Estados Unidos tras los ataques del 11 de septiembre.

''Cuando Bush fue electo, me di cuenta que los valores del país tenían que ser defendidos, pero más aún tras el 11 de septiembre, cuando el presidente silenció toda crítica con la disculpa del antipatriotismo'', dijo el empresario estadounidense, de origen húngaro.

Foto: Rui Ferreira

En su opinión, presentada ante unas 500 personas en el Miami Dade College en el marco de la Feria Internacional del Libro, Soros dijo que ''la campaña de Bush está saboteando la fundamentación de una sociedad libre'', porque ``admitir que se está equivocado es la fundamentación de una sociedad abierta''.

''Después del 11 de septiembre el presidente ha tratado de suprimir todo signo de disensión'', enfatizó.

Soros, quien abogó directamente por la elección del senador demócrata John Kerry, dijo que el presidente sabía que no había ninguna conexión entre Osama Bin Laden y Saddam Hussein, pero aun así invadió a Irak.

''¿Se imaginan lo que piensa el mundo de nosotros cuando escucha decir cosas como que no importa lo que se hace en Irak con tanto que vivamos seguros aquí?'', afirmó.

Pero, ``la verdad es que al violar la ley internacional, el presidente Bush no nos ha hecho más seguros''.

''Toda mi experiencia en democracia me dice que no se puede imponer la democracia por la violencia, e Irak sería el último lugar donde se me ocurriría experimentar con la implantación de la democracia'', añadió.

Soros estimó que la guerra en Irak ``ha hecho mucho daño a Estados Unidos, a nuestra sociedad, pero también a la moral de las tropas, porque no han sido entrenadas como una fuerza de ocupación''.

El empresario y autor de varios libros ha desarrollado una fuerte campaña contra el presidente en los últimos meses.

Foto: Rui Ferreira

Ayer, Soros no negó que quiere ver al presidente fuera de la Casa Blanca.

''Esta no es una elección normal, sino un referendo al mandato del presidente. Si lo reelegimos, no sólo estamos respaldando sus políticas, estamos asumiendo sus consecuencias'', dijo. Es más, ``rechacemos sus políticas, porque sólo así tendremos más apoyo en el mundo''.

(C) 2004 El Nuevo Herald

Carta da América

Hoje fui almoçar com o George Soros. Durante hora e meia ouvi as razões porque decidiu investir metade da sua fortuna na derrota do presidente americano.

Hoje fui almoçar com o George Soros. Durante hora e meia ouvi as razões porque decidiu investir metade da sua fortuna na derrota do presidente americano.

Explicou que tudo se reduz a um facto. Desde o 11 de setembro do ano 2001, que Bush não admite nenhum tipo de crítica e em nome do patriotismo calou toda a voz dissidente. Está a minar as bases de uma sociedade livre porque o direito à diferença é uma das bases das sociedades abertas.

E com isto não foi sequer consecuente com os ideais republicanos. E depois disto nada se pode esperar dele. Se reelegemos a Bush somos responsaveis pelas consecuencias. Foi George Soros hoje ao almoço. Logo ao jantar há mais. Ouça aqui.

Rui Ferreira

quarta-feira, outubro 20, 2004

Carta da América

Isto é muito simples, um fantasma ronda a América, é o fantasma do serviço militar obrigatório. Ninguem sabe como apareçeu, de onde veio. Até acabou por ser mencionado no ultimo debate presidencial.

Isto é muito simples, um fantasma ronda a América, é o fantasma do serviço militar obrigatório. Ninguem sabe como apareçeu, de onde veio. Até acabou por ser mencionado no ultimo debate presidencial.

Ontem telefonei às duas campanhas e as duas dissseram-me que nem Kerry nem Bush se opõem ao recrutamento obrigatório, mas inesperadamente começaram a atacarse uma à outra. Do estilo, a gente pensa que ele disse, nao importa que não tenha dito, de qualquer modo a gente responde já. Enfim, é o delirio.

E como a guerra do Viename deixou muitas marcas e as pessoas ainda se lembram do recrutamento obrigatório e das imagens da frente de batalla que chegavam pelas televisões, a coisa por ter o seu efeito. Ou não fosse um bom boato. Não há dúvida, meus senhores, a Guerra Fria ataca a América eleitoral. Ouça aqui.

Rui Ferreira

Un ejército de abogados listo para pelear los resultados de las elecciones en EEUU

por Deborah Charles / Reuters

Cuatro años después de apurarse para enviar abogados a Florida a fin de librar la batalla del recuento de votos, los partidos Republicano y Demócrata están desplegando miles de expertos legales a lo largo de Estados Unidos previo a las elecciones presidenciales del 2 de noviembre.

Los demócratas dicen que han reclutado a más de 10,000 abogados --muchos de ellos voluntarios-- y que tienen equipos de expertos que pueden desplazarse rápidamente en caso de problemas legales o alguna disputa en las urnas como la del 2000 en Florida.

Los resultados de ese estado fueron determinantes para que el republicano George W. Bush llegara a la Casa Blanca hace cuatro años, tras una amarga contienda legal de cinco semanas, y nuevamente ahora es uno de los diez estados reñidos en la carrera presidencial.

Bush se impuso sobre su contrincante, Al Gore, en Florida en el 2000 por 537 votos después de un discutido recuento de sufragios que terminó en la Corte Suprema de Justicia. Desde entonces Florida aprobó una ley en la que permite que se comience a votar 15 días antes del día de la elección nacional.

’’Vamos a tener cinco equipos de abogados que se puedan desplazar para luchar en cinco recuentos simultáneos’’, dijo Marc Elias, consejero general del senador de Massachusetts John Kerry, el contendiente demócrata de Bush.

’’Eso es una consecuencia de nuestra experiencia en el 2000, cuando estaba claro que ninguna de las partes ... no estaba preparada para tener una operación del tipo de la de Florida, si al mismo tiempo había una competencia reñida en Nuevo México y una carrera cercana en Iowa’’, agregó.

Los demócratas también planean tener un abogado en cada distrito electoral disputado, en cada estado clave, el día de la elección, para enfrentar cualquier acusación de anulación de votos, seguridad en las urnas u otros problemas.

Los republicanos no dijeron cuántos abogados reclutaron, pero posiblemente el número sea similar al de los demócratas.

Las autoridades del partido Republicano dicen que sus abogados estarán vigilando las elecciones para garantizar que se sigan los procedimientos adecuados y que no haya actividades fraudulentas.

La Asociación Nacional de Abogados Republicanos hace unos meses llevó a cabo un curso nacional de entrenamiento sobre la nueva ley electoral y estuvo haciendo diversas actividades de este tipo a nivel estatal.

Un fuerte incremento en el número de votantes registrados podría causar problemas, pues tradicionalmente los nuevos votantes son los que tienen problemas con las máquinas de votación, dijeron los expertos legales.

Ya han surgido disputas legales por algunos votos en ausencia y, en momentos en que una gran cantidad de tropas de Estados Unidos están en el exterior, estos sufragios fuera del país podrían jugar un papel en el resultado final.

Las máquinas de votación electrónica, que están siendo utilizadas por primera vez en una elección presidencial en muchos condados, podrían fallar o sus resultados podrían ser puestos en duda, especialmente donde no hay registros en papel.

Otros desafíos legales podrían surgir también por el uso de boletas provisorias, que bajo la ley federal, ahora deben ser provistas a los votantes si sus nombres no están en los padrones.

Cuatro años después de apurarse para enviar abogados a Florida a fin de librar la batalla del recuento de votos, los partidos Republicano y Demócrata están desplegando miles de expertos legales a lo largo de Estados Unidos previo a las elecciones presidenciales del 2 de noviembre.

Los demócratas dicen que han reclutado a más de 10,000 abogados --muchos de ellos voluntarios-- y que tienen equipos de expertos que pueden desplazarse rápidamente en caso de problemas legales o alguna disputa en las urnas como la del 2000 en Florida.

Los resultados de ese estado fueron determinantes para que el republicano George W. Bush llegara a la Casa Blanca hace cuatro años, tras una amarga contienda legal de cinco semanas, y nuevamente ahora es uno de los diez estados reñidos en la carrera presidencial.

Bush se impuso sobre su contrincante, Al Gore, en Florida en el 2000 por 537 votos después de un discutido recuento de sufragios que terminó en la Corte Suprema de Justicia. Desde entonces Florida aprobó una ley en la que permite que se comience a votar 15 días antes del día de la elección nacional.

’’Vamos a tener cinco equipos de abogados que se puedan desplazar para luchar en cinco recuentos simultáneos’’, dijo Marc Elias, consejero general del senador de Massachusetts John Kerry, el contendiente demócrata de Bush.

’’Eso es una consecuencia de nuestra experiencia en el 2000, cuando estaba claro que ninguna de las partes ... no estaba preparada para tener una operación del tipo de la de Florida, si al mismo tiempo había una competencia reñida en Nuevo México y una carrera cercana en Iowa’’, agregó.

Los demócratas también planean tener un abogado en cada distrito electoral disputado, en cada estado clave, el día de la elección, para enfrentar cualquier acusación de anulación de votos, seguridad en las urnas u otros problemas.

Los republicanos no dijeron cuántos abogados reclutaron, pero posiblemente el número sea similar al de los demócratas.

Las autoridades del partido Republicano dicen que sus abogados estarán vigilando las elecciones para garantizar que se sigan los procedimientos adecuados y que no haya actividades fraudulentas.

La Asociación Nacional de Abogados Republicanos hace unos meses llevó a cabo un curso nacional de entrenamiento sobre la nueva ley electoral y estuvo haciendo diversas actividades de este tipo a nivel estatal.

Un fuerte incremento en el número de votantes registrados podría causar problemas, pues tradicionalmente los nuevos votantes son los que tienen problemas con las máquinas de votación, dijeron los expertos legales.

Ya han surgido disputas legales por algunos votos en ausencia y, en momentos en que una gran cantidad de tropas de Estados Unidos están en el exterior, estos sufragios fuera del país podrían jugar un papel en el resultado final.

Las máquinas de votación electrónica, que están siendo utilizadas por primera vez en una elección presidencial en muchos condados, podrían fallar o sus resultados podrían ser puestos en duda, especialmente donde no hay registros en papel.

Otros desafíos legales podrían surgir también por el uso de boletas provisorias, que bajo la ley federal, ahora deben ser provistas a los votantes si sus nombres no están en los padrones.

terça-feira, outubro 19, 2004

In Florida, It Begins Anew

Early Voting Starts Amid Shadow Left by 2000 Chaos

By Manuel Roig-Franzia

Washington Post

MIAMI -- Bongo drums, rapping preachers and a smattering of all-too-familiar technical difficulties greeted Florida voters Monday as the state's first attempt at early voting in a presidential election opened the 16-day voting season in this critical battleground state.

Thousands of people, many motivated by anger over the botched 2000 presidential election, lined up to cast ballots in Miami, Palm Beach County and other parts of the state roiled by the chaos of the last presidential race. Voters wedged into Miami's cavernous downtown government center and took numbers similar to those used at grocery store deli counters. City officials tried to offer a modicum of privacy by shooing away photographers who jumped rope lines and pushed their lenses within inches of the first voters to cast ballots.

Photo Credit: J. Pat Carter-AP

Voters cast their ballots electronically in a Miami government building. Florida was one of four states to kick off early balloting yesterday.

"The circus is already getting started," said Bruce Detorres, 46, a legal aide to the poor, whose slip of paper identified him as Miami-Dade County voter number 18.

The state was thick with poll watchers attuned to every step of the process and they were spotting flaws throughout the day. Laptops used to verify registrations malfunctioned in Broward County, and computers froze in Orange County, briefly delaying voter verification.

"All I know is that we're not going to let anything slip by us," said state Rep. Shelley Vana (D), who complained after noticing missing pages on an absentee ballot she requested at a Palm Beach County polling place.

Florida's early-voting process, like almost everything about the state's election machinery, has been assailed by complaints this fall. It took an NAACP lawsuit to get additional early-voting sites in Volusia County, where voter advocates complained that the county's single location was too far from high concentrations of African American voters in Daytona Beach.